Abstract: When a private company makes a loan to a shareholder or an associate during an income year, Div 7A of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) can deem the company to have paid a dividend. The dividend is assessable to that shareholder/associate. However, no deemed dividend will arise if the loan is either repaid or placed under a complying loan agreement before the due date for lodgement of the company’s income tax return for that year (or the actual date of lodgement, if earlier). A common way of making each year’s minimum repayment on a Div 7A loan is to set it off against a dividend of the same amount declared by the company. This article sets out an alternative approach whereby the loan is fully repaid at the outset in the same manner, and the client borrows from the bank to pay the top-up tax arising on the dividend. This may actually leave your client better off.

Introduction

Division 7A of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) (ITAA36) is a self-executing set of integrity measures designed to combat the extraction of profits from private companies in a non-taxable form. Such profits have usually only borne 30 cents in the dollar of company tax — far lower than the top personal tax rate of 46.5 cents that the company’s shareholders may be subject to. A common way of extracting the remaining 70 cents in the dollar without incurring further tax is by the company making a loan to shareholders or associates.1

Where a private company makes a loan to a shareholder or an associate during an income year, Div 7A can deem the company to have paid a dividend. The dividend is assessable to that shareholder/associate and subject to income tax.2 However, no deemed dividend will arise if the loan is either repaid or placed under a complying loan agreement before the due date for lodgement of the company’s income tax return for that year (or the actual date of lodgement, if earlier). Complying loan agreements require repayments of principal and interest over a limited number of years.

In other words, if you take money from your private company in the form of a loan, fine, but you must pay it back, plus interest, within certain time limits. Otherwise, it may well be assessed to you as a dividend. This is a common situation confronting many practitioners in assisting private clients with their tax affairs. Now we set out what is probably the most common means used to repay such loans, and then compare that to a novel alternative that may leave a client better off.

The common approach

It is rare for a client to repay the loan back to their company before the lodgement deadline. The money is usually committed to a particular use, or perhaps funds a certain level of lifestyle. This means, quite simply, that the money will not be returned to the company before the lodgement deadline.

Accordingly, the usual way of avoiding a deemed dividend is to execute a complying loan agreement. These require a minimum annual repayment of principal and interest over a term of up to seven years.3

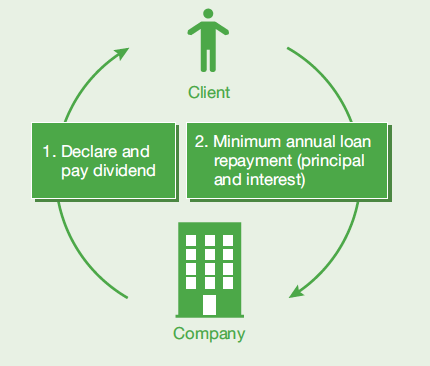

For the above same reasons why the loan itself is rarely repaid in cash, it is also rare for a client to make each year’s minimum repayment by paying money to the company. The more common approach is for the company to declare a fully franked dividend each year equal to the amount of the required repayment. We then have mutually opposed obligations — the client owes that year’s loan repayment to the company, and the company owes the dividend to the client. Both obligations are met, without exchanging money, by way of set-off against each other. This is illustrated as follows:

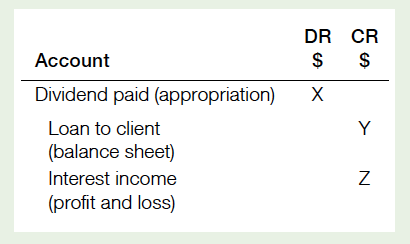

The set-off is typically recorded in the company’s accounts as follows:

The dividend is typically assessed to your client and/or other family members, either directly as the shareholders in the company, or indirectly through a distribution from their discretionary trust shareholder.4 This usually results in a “top-up” tax liability, being the balance of tax from the company rate of 30 cents up to the client’s personal tax rate of up to 46.5 cents (ie up to a further 16.5 cents).

These dividends extract a blend of the company’s existing retained profits and the new addition to retained profits from the interest income. Top-up tax may ultimately have arisen on extracting the company’s existing retained profits in any case. However, additional tax liabilities arise, which stem from the interest on the loan paid into the company. The client is paying this interest into the company, and then back out to himself via the dividend. Where the loan funds have been used for private purposes, the interest cost is not deductible to the client.

The result is that 46.5% tax is borne on that interest income — 30% by the company, and 16.5% top-up tax by the client upon it being circulated out as a dividend as part of the dividend/repayment set-off. The practical effect of this approach is that the client is transferring money from his left pocket to his right pocket, but losing 46.5% along the way in tax.

The more insidious side of this common approach is that these additional tax liabilities may be swept under the carpet, buried among the client’s overall tax obligations. Also, it obscures the fact that the 30 cents tax in the dollar paid by the company on its profits is not the end of the matter; the 70 cents the client takes from the company in the form of a loan is often not yet fully clear of income tax.

Alternative approach

The common approach ultimately produces costs for the client, but how much exactly is not readily apparent until we analyse it or compare to alternatives. One alternative worth considering for a loan made during an income year is this:

- just before the lodgement day, the company declares a fully-franked dividend (provided sufficient franking credits are available) of an amount equal to the entire amount of the loan

- the client repays the loan in full by set-off against the above dividend;5

- the client borrows from a bank to fund the payment of the top-up tax liability that will subsequently arise to him on that dividend;6 and

- the client repays the bank over the same period that it takes to deal with a Div 7A loan under the common approach.

If (1) and (2) are done before the lodgement day deadline, the practical outcome is that Div 7A will have no application. The period of time in (4) for repaying the bank is chosen merely so that we can compare to the typical seven-year Div 7A loan.

The client will of course need to have the capacity to undertake the bank borrowing. This alternative produces different outcomes for the client. The issue in question is which approach leaves the client better off.

Common approach vs alternative approach

We can now take a typical client scenario and compare the common approach to the alternative approach to see which one leaves the client in a better position. This requires tabulating all flows of money to and from the client, including the cost of funding any outflows. In the end, it is simply a matter of which approach leaves your client with more money in his pocket.

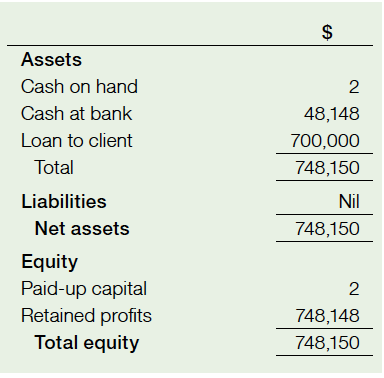

Let’s say your client’s company has the following balance sheet as at 30 June 20127:

The company made a before-tax profit of $1m for the year ended 30 June 2012, and the tax liability for the year at 30% is $300,000. For ease of illustration, let’s say that was fully paid throughout the year in PAYG instalments, leaving no remaining liability at 30 June 2012. So, the company’s after-tax profit for the year is $700,000. There is also $48,148 of retained profits from prior years left in the company. Further, the client has taken all of the 2011-12 after-tax profit out of the company during that year. This is reflected in the typical manner whereby the company has advanced a loan to him totalling $700,000 as at 30 June 2012.

At this point, there are not yet any consequences under Div 7A. Let’s say the company’s 2011-12 income tax return is due on 31 March 2013, and will be lodged on that day. Accordingly, the client has until 30 March 2013 to either repay the loan or execute a complying loan agreement.

For the purposes of this example, we will assume the following:

- the client personally is the sole shareholder in the company;8

- the client is subject to the top personal income tax rate of 46.5%;

- the $700,000 taken from the company is used for private purposes. Therefore, the interest incurred by the client on the Div 7A loan under the common approach will not be deductible;

- the loan funds are not available to repay the loan back to the company, nor is the option of a 25-year real estate-secured loan available;

- ignore any future years’ profits. Funds representing these profits are usually not available for the same reasons that 2011-12’s profit isn’t;

- the client is able to borrow from a bank at an interest rate of 7% to fund the top-up tax liabilities that will arise under each approach; and

- the benchmark interest rate is 7.8% for all years.

The above is typical of many clients’ circumstances. Now we can compare the common approach with the alternative. Let’s start by showing how much money the client is left with under the common approach.

Common approach

Many practitioners would be well familiar with this approach. A complying loan agreement will be executed by 30 March 2013, with a term of seven years. The first annual repayment of principal and interest is due by 30 June 2013, and a repayment required in each of the subsequent six income years to fully repay the loan.

The minimum annual repayment required under the complying loan agreement, using the formula in s 109E(6) ITAA36, is $133,532. Repayments are usually made on 1 July each year, rather than at any other time during the year. This reduces the daily loan balance on which interest is calculated for that year. The reduced interest over the life of the loan manifests in the loan balance at the time of the seventh and final repayment being less than the above minimum repayment. Accordingly, the final repayment only needs to be an amount equal to that final loan balance.

The timing of making each year’s repayment makes no difference to the timing of the top-up tax on the dividend offset, as the dividend will be assessed that financial year, irrespective of the point in time it is paid in the year.

The minimum annual repayment required under the complying loan agreement, using the formula in s 109E(6) ITAA36, is$133,532. Repayments are usually made on 1 July each year, rather than at any other time during the year. This reduces the daily loan balance on which interest is calculated for that year. The reduced interest over the life of the loan manifests in the loan balance at the time of the seventh and final repayment being less than the above minimum repayment. Accordingly, the final repayment only needs to be an amount equal to that final loan balance.

The timing of making each year’s repayment makes no difference to the timing of the top-up tax on the dividend offset, as the dividend will be assessed that financial year, irrespective of the point in time it is paid in the year.

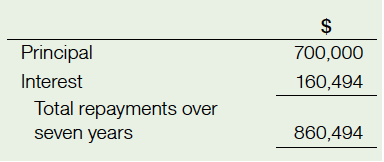

Let’s say the first repayment of $133,532 is made on 31 March 2013 (ie just after it is decided to put a complying loan agreement in place), and the second to sixth repayments are made on each 1 July in 2013 through to 2017. On that basis, the loan balance will be reduced to $59,302 at the time of the seventh and final repayment on 1 July 2018. Accordingly, that is the payment made on that date and this will fully extinguish the loan. The six repayments of $133,532 and one of $59,302 total $860,494. The principal– interest breakdown over the loan period is as follows:

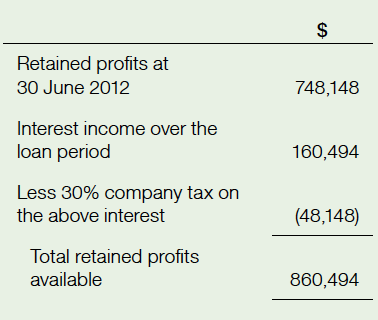

Accordingly, by 1 July 2018, the $700,000 loan principal will be repaid to the company, plus $160,494 in assessable interest income. Each year’s repayment is effected by set-off against a fully franked dividend declared by the company(6 x $133,532 and 1 x $59,302). The $160,494 of interest income earned by the company, less 30% company tax, will add to the pool of retained profits. This will provide sufficient after-tax profits to declare the required $860,494 in dividends over the loan period for set-off against the repayments totalling to the same amount. This is reconciled as follows:

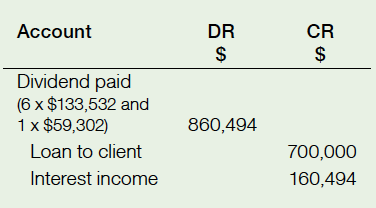

Further, the current cash balance in the company of $48,148 will be used to pay the company tax on the interest income. The total dividend/repayment set-off over the loan period is recorded as follows:

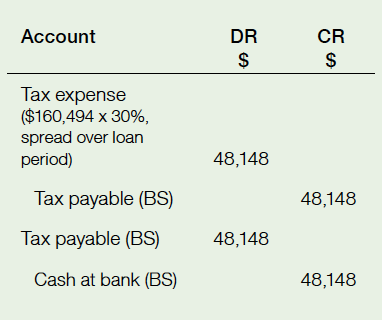

The total company tax liability and payment over the loan period is recorded as follows:

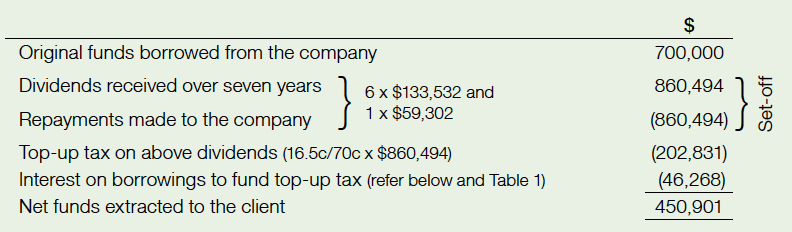

The $748,148 of retained profits in the company as at 30 June 2012 will be fully extracted by the end of the loan period. Now we set down all flows of money from the client’s individual perspective:

On the basis that none of the original $700,000 taken from the company is available, the client somehow has to fund each year’s top-up tax liability. There is a real cost to the client here, such as interest on borrowings to fund the top-up tax. Alternatively, there is an opportunity cost by taking funds invested elsewhere (including future years’ profits) to pay the tax, thus depriving the client of income from those funds. Such funding costs must be factored into both approaches in order to make a meaningful comparison. For this example, we have measured these funding costs in the form of interest on borrowings to fund the tax liabilities. What is important is to be consistent with both approaches so that you can compare the outcomes for the client.

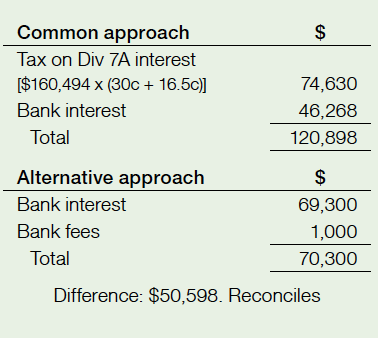

Each $133,532 dividend will have a top- up tax liability of $31,475 ($133,532 x 16.5c/70c) and the final dividend of $13,981 ($59,302 x 16.5c/70c), totalling $202,831. Table 1 sets out the calculation of the interest cost on the accumulating debt to fund each successive year’s top-up tax liability. We are assuming that each year’s tax is payable the following April, and that the $202,831 debt is repaid to the bank in April 2020. The interest paid over that time totals $46,268.

The client is ultimately left with the net benefit of $450,901 extracted from the company. What is happening here is a trade-off. The client is incurring additional tax liabilities, arising essentially by paying interest to himself, plus the interest cost of borrowing to fund those additional taxes. This is in return for stretching out dealing with the $700,000 loan over seven years. Now we have a measured outcome against which we can compare the alternative approach.

Alternative approach

We intuitively know that a short burst of pain from ripping off a band-aid is better than slowly — and agonisingly — peeling it off. This may well be just as applicable to dealing with a Div 7A loan.

The alternative approach does not involve repaying the loan under Div 7A with interest. Rather, it is repaid in full just before the lodgement day by dividend set-off. Accordingly, the additional tax liabilities arising on the Div 7A interest under the common approach do not feature in this approach — the only tax liability is on the lone dividend used to repay the loan. That is, the client won’t be shuffling money between his pockets, and thus won’t be triggering the tax cost of doing so.

However, we will see that, while the alternative approach has a lower tax liability, it has higher interest funding costs over an equivalent period of time. Thus, the question we seek to answer is who the cheaper alternative is: the Commissioner of Taxation or the bank?

The alternative approach in our example deals with the $700,000 loan made in 2011-12 by doing the following:

- the company declares a fully franked dividend of $700,000 on 30 March 2013;

- the client repays the $700,000 loan on the same day by way of set-off against the entitlement to the above dividend;

- a top-up tax liability on the above dividend of $165,000 (16.5c/70c x $700,000) will arise to the client for the 2012-13 income year, payable in, say, April 2014;

- again, we assume that none of the original $700,000 taken from the company is available. Accordingly, the client borrows $165,000 from the bank to pay the top-up tax; and

- the client pays, say, interest-only at 7% on the above borrowing, and then repays the borrowing to the bank in April 2020 (ie same time frame as the common approach)

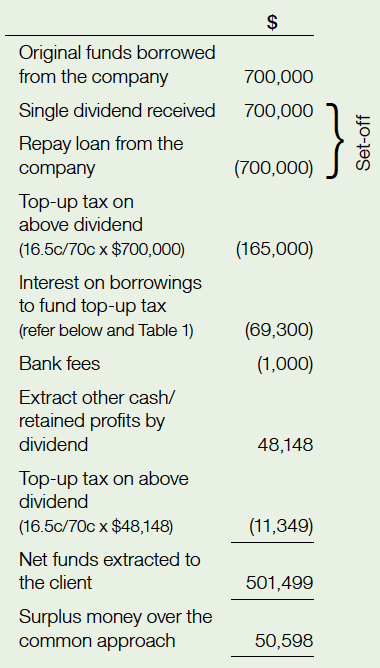

Again, we set down the cash flows over the seven years from the client’s individual perspective:

Similarly to the common approach, we are assuming that none of the original $700,000 taken from the company is available. Accordingly, the client funds the $165,000 top-up tax liability by a single borrowing from the bank. That produces an annual interest cost of $11,550 (ie $165,000 x 7%), totalling $69,300 by April 2020 per Table 1. The $165,000 debt is then paid back to the bank at that time. We have now measured the bank interest costs up to April 2020. This equates with the time frame to deal with the Div 7A loan under the common approach, enabling a meaningful comparison.

As the company incurs no tax liability under this approach, the remaining $48,148 of cash/retained profits is available to the client under this approach. Accordingly, it is extracted into the client’s hands, net of the $11,349 top-up tax.

The result is that, compared to the common approach, the client has $50,598 more cash in his hands. Another way of putting it is that the whole exercise of dealing with the $700,000 taken from the company has cost the client $50,598 less.

Reconciling the difference

We can reconcile the difference in outcomes between the two approaches by extracting what is different between them. Although not readily apparent from the tables above, identical outcomes from both approaches include $165,000 of top-up tax from extracting the 2011-12 profit, and top-up tax on extracting the $48,148 cash. It actually comes down to only two items for each approach that account for the difference, reconciled as follows:

As previously discussed, the common approach produces a 46.5% tax liability on the Div 7A interest, which, in the end, is money that the client has basically paid to himself. The alternative approach bypasses Div 7A altogether, and so doesn’t produce this additional tax liability. However, your client will pay more interest to the bank. In summary, the tax and interest costs under the common approach exceed the interest and bank fees under the alternative approach.

So, while the alternative approach causes the client to pay $24,032 (ie $70,300 – $46,268) more to the bank, he pays $74,630 less in tax. The difference is the $50,598 saving. Your client and the bank win at the expense of the Commissioner. Of course, this is just one year. Applying the alternative approach instead of the common approach over a number of years can accumulate substantial savings for the client.

Calculating the above amounts really only requires doing the following three things:

- create the spreadsheet in Table 1;

- work out the total Div 7A interest over the loan period, times the tax rate; and

- estimate the bank fees.

So, we now have an answer to the question posed earlier — the bank is cheaper than the Commissioner. It is worth noting that the net tax saving arises more so from making an informed financial decision, rather than tax planning. The irony is that this arises from doing exactly what the government wants you to do under Div 7A’s unwritten policy intent: extract company profits by dividends, not loans.

Time value of money

The above flows of money are measured in the actual dollar amounts that will arise over time. This serves the purposes of comparing and reconciling the two approaches, without overcomplicating things. However, the flows of money do happen over a period of years. Accordingly, it is reasonable to consider whether the time value of money factor works against the alternative approach and/or in favour of the common approach. If it does, the gap between the two approaches may be illusory. The only way to check this is to discount all money flows to their present value. While we’re at it, you would also include an after-tax income amount earned on the $48,148 sitting in the company (which progressively diminishes under the common approach as it is used up to pay the company tax).

The present value and after-tax income calculations have not been shown here, but the surplus money under the alternative approach, as measured in present value dollars, is about $43,000. Don’t let that confuse things — the client will still pocket more than $50,000 in actual dollars over the seven years. This exercise merely reflects that amount in today’s dollars, and confirms that the outcome measured in actual dollars is very real indeed.

Variations in interest rates

Higher overall rates

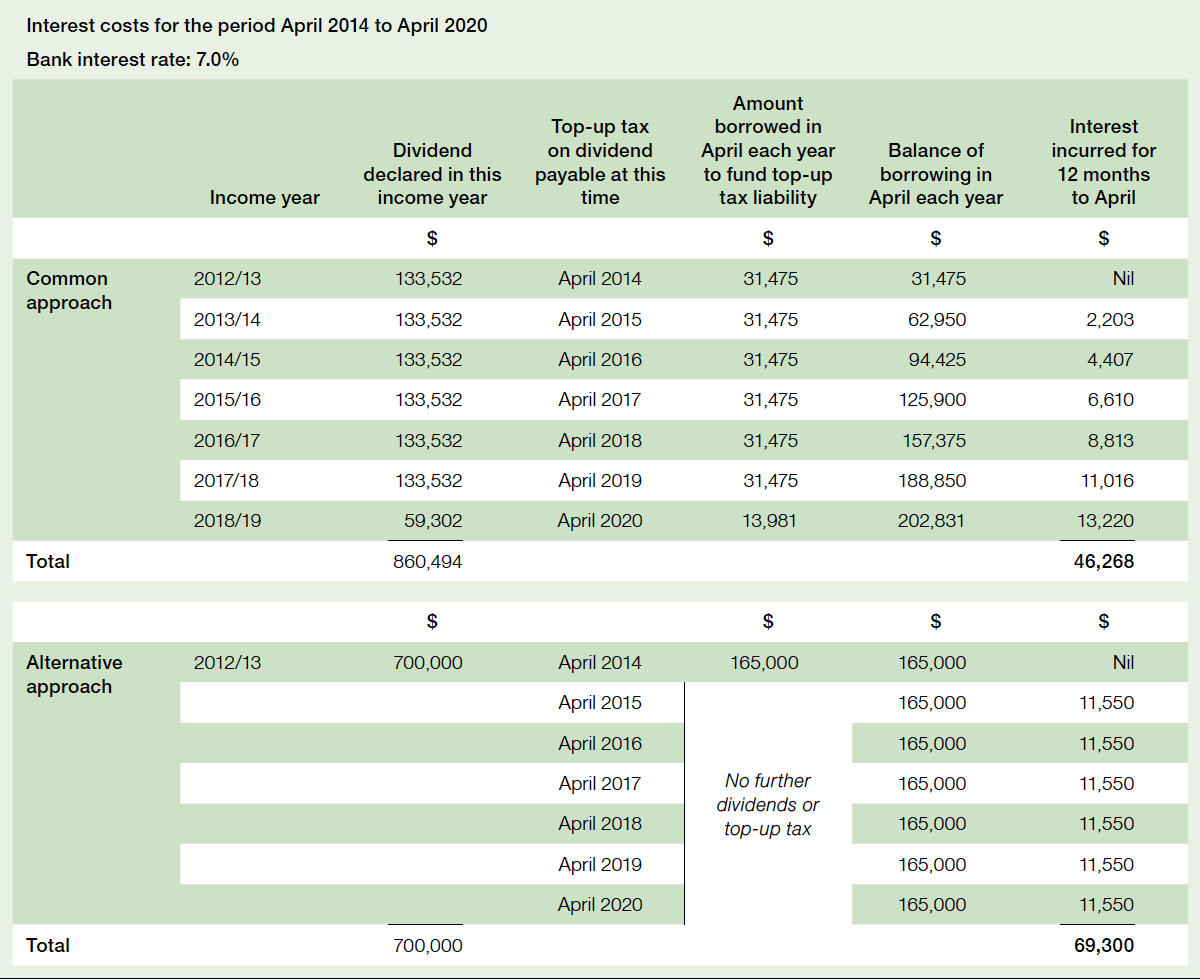

How do the approaches compare in a higher overall interest rate environment? That is, where both bank and benchmark interest rates are higher. The only difference for the alternative approach is that the bank interest cost rises; everything else remains the same, as they are unaffected by interest rates.

In contrast, both interest rates directly or indirectly influence the outcomes for every component of the common approach, except the original Div 7A loan amount itself. The Div 7A interest paid to the company will be higher, and therefore the required offset dividends will be higher.

These result in the income tax liabilities being higher. In addition, the bank interest cost will be higher; first because of having to borrow more to fund the higher tax liabilities, and second because of the higher interest rate itself on those larger borrowings. This compounding effect on the costs under the common approach means that higher overall interest rates widen the gap between the two approaches.

Higher bank rate

What if your client cannot borrow at a secured rate like 7%? If your client could only borrow at a higher, unsecured rate of interest, the bank interest cost for both approaches will rise — but it will rise faster under the alternative approach. In our example, all other components will remain the same, as they are either unaffected by interest rates or are determined from the benchmark rate, which we are leaving unchanged.

All that is required is to increase the bank interest rate in Table 1 and recalculate the interest cost for each approach — easily done by trial and error in the Excel spread sheet. This is shown in Table 2. Substituting the newly calculated interest cost reveals that the amount of money left in the client’s hands under the alternative approach eventually becomes equal to the common approach at an interest rate of about 22.3%. In other words, the client in our example can borrow at an interest rate of up to 22.3% to fund the $165,000 top-up tax liability under the alternative approach, and will still be better off, compared to the common approach.

Again, these amounts are measured in nominal dollars. However, when the money flows are discounted to their present value, the interest rate ceiling is not materially different in any case.

Value-add opportunity

It is fortunate that Div 7A allows time ahead of the lodgement deadline for any particular year to decide what to do about a loan made during that year. This presents an opportunity to offer to your client to undertake this type of analysis, and leaves time to investigate bank lending options or other means to fund the costs. Ultimately, choosing between alternatives is your client’s decision, but one made with comfort when the outcomes of each alternative are quantified and thus comparable.

This exercise also doesn’t hold up completing the annual compliance work. In fact, it can be done quite independently of it, anytime before the lodgement deadline.

You can also switch the remaining balance of an existing unsecured Div 7A loan part way through its seven-year term over to the alternative approach. However, the cost savings diminish as you go further into the loan term.

Other matters

The overarching point is educating clients that, while they can access their company’s after-tax profits of 70 cents in the dollar, these funds ultimately come with a potential further tax impost of up to 16.5 cents. Understanding this helps clients to manage the extraction of profits from their companies, including appreciating any savings achieved, such as under the alternative approach.

The gap between the two approaches lessens where a client falls within one of the personal tax rates below 46.5%. However, that generally holds true only if we are considering a single income year.

If a client has accumulated several years of Div 7A loans, they all require a minimum repayment each year. The total of these repayments per year, paid by way of set-off against a dividend, may well push the client into the top tax bracket in any case. So, if the client will be in the top tax bracket anyway, the alternative approach may still present the saving opportunity as set out above.

Conclusion

The common approach set out above is a convenient and widely used method of dealing with a Div 7A loan, but is not necessarily the best approach in any given circumstance. The alternative approach set out here is merely one alternative way to deal with a Div 7A loan. Estimating and comparing the outcomes from the two approaches is not particularly onerous — it requires working out the amounts in each approach that make all the difference as shown in the reconciliation table above.

This article has demonstrated how to work them out, and that can be applied to any client’s circumstances to estimate the savings achievable. But there may also be other worthwhile alternative approaches. This presents a real opportunity to add value for clients and save them some money.

Table 1: Interest costs to fund the top-up tax liabilities

Table 2: What bank interest rate results in the alternative approach equalling the common approach?

References

- Div 7A also applies to payments and debts forgiven by a company. However, the focus here is on loans.

- The amount of any deemed dividend is limited to the company’s “distributable surplus”.

- The term can be up to 25 years with appropriate real estate security. However, the vast majority of Div 7A loans are unsecured, and thus limited to seven years.

- In many cases, your client (the borrower) may not be the sole shareholder in the company, or a shareholder at all. A discretionary trust, for example, is often the preferred choice to own a private company. However, we are generally dealing with closely held companies and trusts under your client’s control. Accordingly, the dividend in such cases is typically made to flow through interposed shareholder entities to arrive at your client, who can then use that entitlement to set-off against the repayment obligation. Where dividends will flow through a trust shareholder, clients must be mindful of the new requirement in s207-58(1) of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) to document distributions of franked dividends in the trust records prior to year end.

- Or, for example, by set-off against the client’s distribution entitlement to the dividend through a discretionary trust shareholder.

- Or trust distribution entitlement per above.

- In practice, this example is equally applicable to a loan made by a trust with an unpaid present entitlement (whether pre-16 December 2009 or later on sub-trust) owing to a corporate beneficiary.

- As noted above, it equally works in practice where close family members or a discretionary trust are the shareholders.