Please note: This article was written in 2018. Contact our Nexia team for the latest advice.

This publication explores some of the potential effects of the new revenue standard on the Building & Construction (B&C) sector. It supplements our Accounting Update Applying AASB 15 Revenue and should be read in conjunction with that publication.

Applying to for-profit entities for financial years commencing from 1 January 2018, AASB 15 Revenue from Contracts with Customers replaces AASB 118 Revenue, AASB 111 Construction Contracts and four related interpretations, including AASB Interpretation 115 Agreements for the Construction of Real Estate.

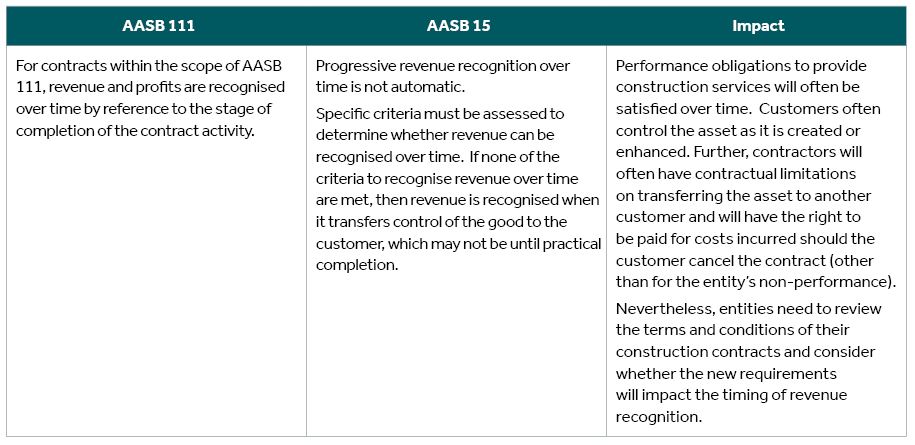

AASB 15 introduces new concepts and definitions of contract revenue and contract costs. A key change is that under AASB 111, revenue from all construction contracts within the scope of that standard was recognised on a percentage of completion basis. However, under AASB 15 there is no automatic right to recognise revenue on a percentage of completion basis, and revenue recognition is only permitted where certain criteria are met.

In this publication, we highlight some of the key impacts arising from the introduction of AASB 15 to entities in the B&C sector. While some B&C entities will find that applying the new Standard will result in an accounting outcome that is similar to the percentage of completion basis described in AASB 111, others may need to change their revenue recognition policies and practices.

Identify the contract

A contract with a customer is within the scope of AASB 15 when it creates enforceable rights and obligations regarding the goods or services to be transferred; the payment terms are identified; the contract has commercial substance and the parties are committed to perform their respective obligations; and it is probable that the entity will collect the consideration to which it will be entitled under the contract.

AASB 15 includes requirements on when:

- two or more contracts should be combined and accounted for together;

- one contract should be segmented and accounted for separately as two or more contracts; and

- a contract modification (such as changes and variations) should be recognised.

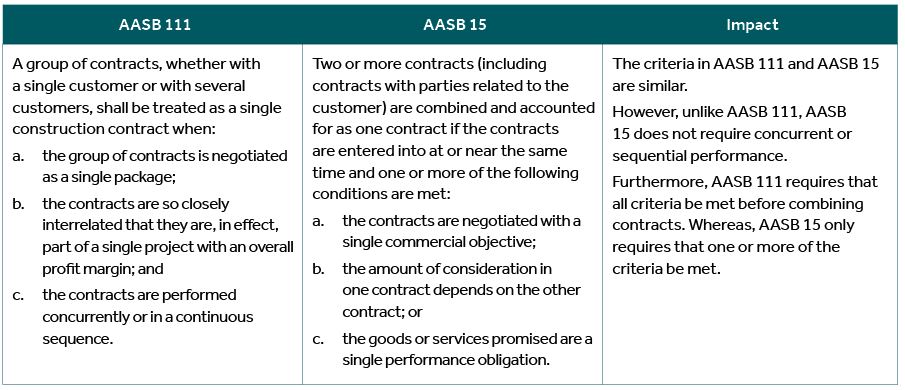

Combining contracts

Entities will need to assess their contractual arrangements to determine whether any change to combining individual contracts is required.

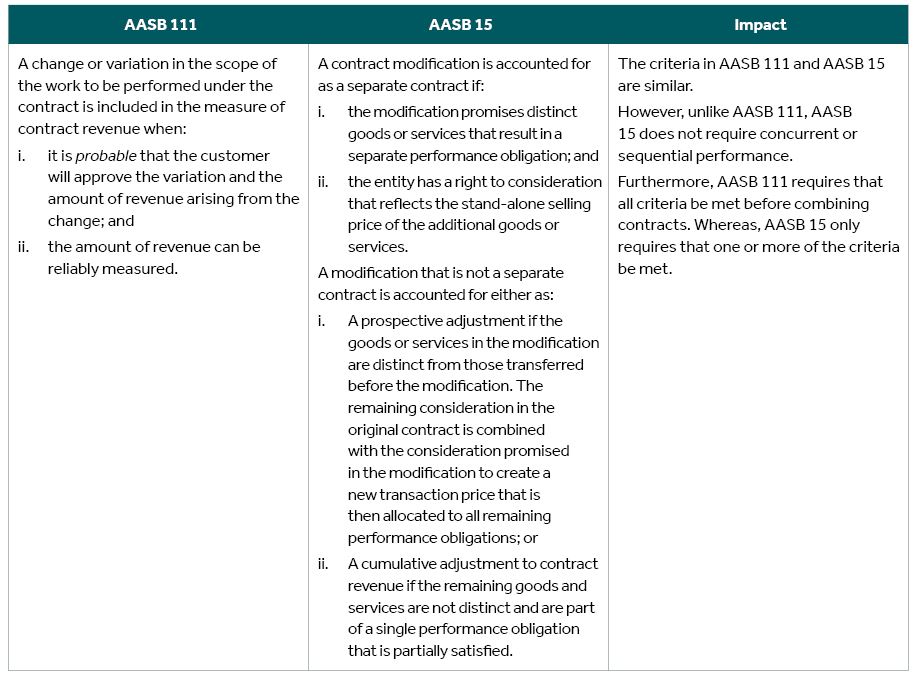

Contract modifications

A contract modification is a change in the scope or price (or both) of a contract that is approved by the parties to the contract. An entity may have to account for a contract modification prior to the parties reaching final agreement on changes in scope and pricing. Instead of focusing on the finalisation of a modified agreement, AASB 15 focuses on whether the rights and obligations of the parties that are changed are enforceable.

Example — Unapproved Change in Scope and Price (AASB 15.IE42-IE43)

An entity enters into a contract with a customer to construct a building on customer-owned land. The contract states that the customer will provide the entity with access to the land within 30 days of contract inception.

However, the entity was not provided access until 120 days after contract inception because of storm damage to the site that occurred after contract inception. The contract specifically identifies any delay (including force majeure) in the entity’s access to customer-owned land as an event that entitles the entity to compensation that is equal to actual costs incurred as a direct result of the delay. The entity is able to demonstrate that the specific direct costs were incurred as a result of the delay in accordance with the terms of the contract and prepares a claim. The customer initially disagreed with the entity’s claim.

The entity assesses the legal basis of the claim and determines, on the basis of the underlying contractual terms, that it has enforceable rights. Consequently, it accounts for the claim as a contract modification in accordance with paragraphs 18–21 of AASB 15. The modification does not result in any additional goods and services being provided to the customer. In addition, all of the remaining goods and services after the modification are not distinct and form part of a single performance obligation.

Consequently, the entity accounts for the modification in accordance with paragraph 21(b) of AASB 15 by updating the transaction price and the measure of progress towards complete satisfaction of the performance obligation. The entity considers the constraint on estimates of variable consideration in paragraphs 56–58 of AASB 15 when estimating the transaction price.

Hence, once the entity determines that the revised rights and obligations are enforceable, the entity is required to account for the contract modification, even if the customer has not formally approved the change. This will be a matter of considering all relevant facts and circumstances of the arrangement.

A contract modification may exist where the parties have approved a change in the scope of the contract but have not yet agreed the change in price. In that case, the entity applies the guidance in AASB 15 relating to determining the transaction price and measuring variable consideration (refer section ‘Determine the transaction price’).

An entity must determine whether the modification creates a new contract or whether it will be accounted for as part of the existing contract. The determination of a new or separate contract is driven by whether the modification results in the addition of distinct goods or services, priced at their stand-alone selling prices.

Identify the performance obligations in the contract

At contract inception, it is necessary to identify all the distinct performance obligations within the contract. Separate performance obligations represent promises to transfer to the customer either:

- A good or service (or a bundle of goods and services) that is distinct; or

- A series of distinct goods and services that are substantially the same and have the same pattern of transfer to the customer.

If those goods or services are distinct, the promises are performance obligations and are accounted for separately. A good or service is distinct if the customer can benefit from the good or service on its own or together with other resources that are readily available to the customer and the entity’s promise to transfer the good or service to the customer is separately identifiable from other promises in the contract.

The criteria in AASB 15 for identifying performance obligations differ from those in AASB 111, which could result in different conclusions about the separately identifiable components. For example, under AASB 111 a contractor may consider an entire contract to be a single component, but under AASB 15, it may determine that the contract contains two or more performance obligations that would be accounted for separately. These judgements may be more complex when, for example, a construction contract also includes design, engineering or procurement services.

Principal versus agency

AASB 15 states that when other parties are involved in providing goods or services to an entity’s customer, the entity must determine whether its performance obligation is to provide the good or service itself (i.e., the entity is a principal) or to arrange for another party to provide the good or service (i.e., the entity is an agent). The determination of whether the entity is acting as a principal or an agent will affect the amount of revenue the entity recognises. That is, when the entity is the principal in the arrangement, the revenue recognised is the gross amount to which the entity expects to be entitled. When the entity is the agent, the revenue recognised is the net amount the entity is entitled to retain in return for its services as the agent.

It is not always clear which party is the principal in a contract and careful consideration of the facts and circumstances of an arrangement is required. An entity is deemed to be acting as a principal if it obtains control of any one of the following:

- a good or another asset from the other party that it then transfers to the customer;

- a right to a service to be performed by the other party, which gives the entity the ability to direct that party to provide the service to the customer on the entity’s behalf; or

- a good or service from the other party that it then combines with other goods or services in providing the specified good or service to the customer. For example, if an entity provides a significant service of integrating goods or services provided by another party into the specified good or service for which the customer has contracted, the entity controls the specified good or service before that good or service is transferred to the customer. This is because the entity first obtains control of the inputs to the specified good or service (which includes goods or services from other parties) and directs their use to create the combined output that is the specified good or service.

In addition, indicators that an entity is acting as principal include:

- the entity is primarily responsible for fulfilling the contract (the promise to provide the specified good or service). This typically includes responsibility for the acceptability of the specified good or service;

- the entity has inventory risk before the specified good or service has been transferred to a customer or after transfer of control to the customer (for example, if the customer has a right of return); and

- the entity has discretion in establishing the price for the specified good or service.

In some elements of construction contracts, it may not always be obvious whether developer is acting as principal or agent. For example, individual arrangements with sub-contractors and material suppliers may vary such that the developer is only acting as agent for the customer. Arrangements will need to be examined in light of the above criteria to determine whether the entity is acting in the capacity of principal or agent.

Determine the transaction price

An entity must determine the amount of consideration it expects to receive in exchange for transferring promised goods or services to a customer. Usually, the transaction price is a fixed amount. However, the transaction price can vary because of discounts, rebates, price concessions, refunds, volume bonuses, or other factors. An entity should consider the effects of variable consideration and include those elements in the transaction price.

To estimate the total variable contract price, an entity applies the method below that better predicts the amount of consideration to which it will be entitled:

- The expected value—the sum of probability-weighted amounts in a range of possible amounts; or

- The most likely amount—the single most likely amount in a range of possible outcomes (i.e. the single most likely outcome of the contract).

A measure of variable consideration is included in the transaction price only to the extent that it is highly probable that a significant reversal in the amount of cumulative revenue recognised will not occur.

The ‘highly probable’ threshold is a higher hurdle than ‘probable’ used in AASB 111. This is likely to result in revenue relating to variable consideration being deferred and recognised later compared to AASB 111.

When a contract has a significant financing element, the effects of the time value of money are taken into account by adjusting the transaction price and recognising interest income over the financing period. However, a finance component does not exist if the timing of the future billings coincides with when the entity expects to perform under the contract. Consequently, entities will have to evaluate whether a contract includes a significant financing component.

Example – Withheld Payments on a Long-Term Contract (AASB 15.IE141-IE142)

An entity enters into a contract for the construction of a building that includes scheduled milestone payments for the performance by the entity throughout the contract term of three years. The performance obligation will be satisfied over time and the milestone payments are scheduled to coincide with the entity’s expected performance. The contract provides that a specified percentage of each milestone payment is to be withheld (ie retained) by the customer throughout the arrangement and paid to the entity only when the building is complete.

The entity concludes that the contract does not include a significant financing component. The milestone payments coincide with the entity’s performance and the contract requires amounts to be retained for reasons other than the provision of finance in accordance with paragraph 62(c) of AASB 15. The withholding of a specified percentage of each milestone payment is intended to protect the customer from the contractor failing to adequately complete its obligations under the contract.

Allocate the transaction price to the performance obligations

Where a contract contains more than one distinct performance obligation, the transaction price is allocated to each distinct performance obligation on the basis of relative stand-alone selling price. The best evidence of stand-alone selling price is the price at which the good or service is sold separately by the entity.

If a stand-alone selling price is not directly observable, an entity should estimate a stand-alone value taking into account market conditions, entity-specific factors and information about the customer or class of customer. This could be done by using an ‘adjusted market assessment approach’ which may include referring to competitors’ prices for similar goods or services; or an ‘expected cost plus approach’ in which an entity estimates its costs to satisfy that performance obligation and then adds an appropriate margin.

Determining whether the consideration arising from a contract modification reflects the stand-alone selling price of the activities will require significant judgement.

Example – Modification of a construction contract

ConstructCo agrees to construct an office building on a customer’s land for $10 million. During construction, the customer determines that an additional carpark is needed at the location. The parties agree to modify the contract to include the construction of the carpark, to be completed within three months of completion of the office building, for a total price of $11 million.

Scenario A

When the contract is modified, an additional $1 million is added to the consideration that ConstructCo will receive. ConstructCo considers the factors in AASB 15.76-.80 and determines that the additional $1 million reflects the stand-alone selling price at contract modification, adjusted for the particular circumstances of the contract.

Assuming that ConstructCo determines that the construction of the carpark is a distinct performance obligation, the carpark addition is accounted for as a new (separate) contract in accordance with AASB 15.20 with a transaction price of $1 million. The modification does not affect the accounting (i.e., the transaction price and revenue recognition) for the office building contract.

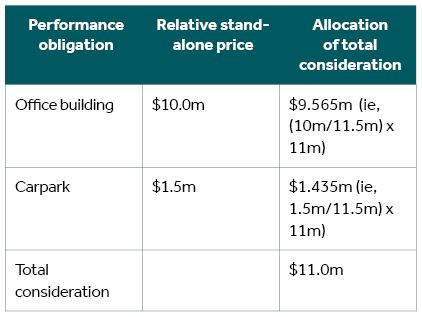

Scenario B

As in Scenario A, the contract is modified when ConstructCo agrees to build the carpark and the customer agrees to pay an additional $1 million. Again assume that ConstructCo determines that the construction of the carpark is a distinct performance obligation and that it transfers control of each asset over time. However, applying the factors in AASB 15.76-.80, ConstructCo determines that the additional $1 million does not reflect the stand-alone selling price at contract modification, which it determines to be $1.5 million.

As a result, ConstructCo accounts for the addition as a modification of the original contract because the scope of the contract has changed and the price increases by an amount that does not reflect the stand-alone selling price for the additional promised goods and services (AASB 15.20).

The revised transaction price of $11 million is allocated between the two performance obligations in the modified contract (being the original incomplete performance obligation to construct the office building and the new performance obligation to construct the carpark). The transaction price is allocated based on the relative stand-alone selling prices of each performance obligation. Any revenue previously recognised for the office building is adjusted on a cumulative catch-up basis to reflect the allocated transaction price. Revenue from the construction of the carpark (i.e., a separate performance obligation) is recognised based on the appropriate measure of progress.

Assuming that the office building was 50% complete at the time of the carpark modification and that no work had commenced on the carpark, ConstructCo would remeasure its cumulative revenue recognised at that point in time from $5.0m (50% of $10.0m) to $4.782m (50% of $9.565m). For the purpose of recognising revenue under AASB 15, the consideration allocated to the construction of the car park is therefore $1.435 million, notwithstanding the contracted amount may be stated at $1 million.

Entities will need to carefully evaluate performance obligations at the date of a modification to determine whether the remaining goods or services to be transferred are distinct and the prices are commensurate with their stand-alone selling prices. This assessment is important because the accounting treatment can vary significantly depending on the conclusions reached.

Recognise revenue as the performance obligations are satisfied

An entity recognises revenue when (or as) it satisfies a performance obligation by transferring a control of a promised good or service to a customer. A performance obligation may be satisfied at a point in time or over time.

If a performance obligation is not satisfied over time, an entity satisfies the performance obligation at a point in time. The point in time is determined as the date on which the customer obtains control of the promised asset. The facts and circumstance of an arrangement needs to be analysed to determine when control of the promised asset is transferred.

For each performance obligation satisfied over time an entity recognises revenue over time by measuring the progress towards complete satisfaction of that performance obligation. The objective when measuring progress is to depict an entity’s performance in transferring control of goods or services promised to a customer (ie the satisfaction of an entity’s performance obligation).

Methods of measuring progress include output methods and input methods.

Output methods recognise revenue on the basis of direct measurements of the value to the customer of the goods or services transferred to date relative to the remaining goods or services promised under the contract. Output methods include methods such as surveys of performance completed to date, appraisals of results achieved, milestones reached, time elapsed and units produced or units delivered. As a practical expedient, if an entity has a right to consideration from a customer in an amount that corresponds directly with the value to the customer of the entity’s performance completed to date (for example, a service contract in which an entity bills a fixed amount for each hour of service provided), the entity may recognise revenue in the amount to which the entity has a right to invoice.

Input methods recognise revenue on the basis of the entity’s efforts or inputs to the satisfaction of a performance obligation (for example, resources consumed, labour hours expended, costs incurred, time elapsed or machine hours used) relative to the total expected inputs to the satisfaction of that performance obligation. If the entity’s efforts or inputs are expended evenly throughout the performance period, it may be appropriate for the entity to recognise revenue on a straight-line basis. However, care needs to be taken in applying an input method where may not be a direct relationship between an entity’s inputs and the transfer of control of goods or services to a customer (eg, where the cost incurred is not proportionate to the entity’s progress in satisfying the performance obligation). In that instance, an adjustment to the measure of progress may be required when using a cost-based input method.

Contract costs

The Standard differentiates between the costs to obtain a contract and the costs to fulfil a contract.

Costs to obtain a contract

The incremental costs of obtaining a contract can be recognised as an asset provided the entity expects to recover those costs. The incremental costs of obtaining a contract are those costs that an entity incurs to obtain a contract with a customer that it would not have incurred if the contract had not been obtained (for example, a sales commission). Costs to obtain a contract that would have been incurred regardless of whether the contract was won or obtained are recognised as an expense as incurred.

AASB 111 does not require costs to be incremental in order to be capitalised, provided they are attributable to the contract (eg, due diligence and internal costs) and are probable of recovery under the contract. Consequently, AASB 15 may exclude some initial contract related costs that had been capitalised under AASB 111.

Example – Tender costs

Company A incurs the following costs in relation to tendering for a contract. All costs are expected to be recovered from contract revenues:

Staff time to prepare the proposal $30,000

External legal fees for due diligence $5,000

Travel costs for site visit $7,000

Commissions to sales employees on contract signing $10,000

Total costs incurred $52,000

Under AASB 15, Company A recognises a contract asset for $10,000, being the incremental sales commission costs of obtaining the contract. Although the other costs are related to obtaining the contract, those costs would have been incurred regardless of whether the entity was successful in its bid. Hence, they are not incremental to obtaining (ie, signing) the contract. Under AASB 111, Company A determined that these costs were attributable to the contract and recognised an asset of $52,000.

Costs to fulfil a contract

The costs incurred to fulfil a contract are capitalised as an asset (commonly referred to as work in progress). Such costs are those directly related to the contract and include:

- direct labour and materials;

- allocations of costs that relate directly to the contract or to contract activities (for example, costs of contract management and supervision, insurance and depreciation of tools and equipment used in fulfilling the contract);

- costs that are explicitly chargeable to the customer under the contract; and

- other costs that are incurred only because an entity entered into the contract (for example, payments to subcontractors).

The capitalised costs are then amortised in profit and loss on a systematic basis that is consistent with the transfer to the customer of the goods or services. Such amortisation (representing cost of sales) will be recognised either:

- over time (where the performance obligation to transfer the promised goods or service, and therefore recognition of the related revenue, is recognised over time); or

- in its entirety at a point in time (where the performance obligation to transfer the promised goods, and therefore recognition of the related revenue, is recognised at a point in time).

Loss-making contracts

Unlike AASB 111, AASB 15 does not contain specific requirements relating to loss-making contracts. Rather, the requirements of AASB 137 Provisions, Contingent Liabilities and Contingent Assets are applied, which requires a provision for an onerous contract to be recognised.

Initial deposits

In some contracts, an entity charges a customer an upfront deposit at or near contract inception, for example, a 20% deposit on signing a construction contract.

In these cases, an entity should assess whether the fee relates to the transfer of a promised good or service at contract inception. Sometimes, even though the fee relates to an activity that the entity is required to undertake at or near contract inception to fulfil the contract, that activity does not result in the transfer of a promised good or service to the customer. Instead, the initial fee is an advance payment for future goods or services and, therefore, would be recognised as revenue when those future goods or services are provided.

Warranties and retentions

Many construction contracts contain retentions. Amounts that relate to that portion of the transaction price which is unpaid by the customer for a period of time subsequent to practical completion to cover defects or faults that may arise during the retention period may represent variable consideration. In this case the requirements relating to the recognition of variable consideration apply.

In the absence of retentions, an entity may still be required to repair or replace products that develop faults within a specified period from the time of sale in accordance with statutory requirements. Such statutory warranties are not recognised as separate performance obligations under AASB 15. Instead, they are measured and recognised as separate liabilities in accordance with AASB 137.

However, where an entity either sells separately or negotiates separately with a customer so that the customer can choose whether to purchase the warranty coverage, or an extended warranty, the warranty provides a service to the customer in addition to the promised product. Consequently, this type of extended warranty is a separate performance obligation which is accounted for in accordance with AASB 15.

Disclosures

Extensive qualitative and quantitative disclosures are required by AASB 15. These disclosures are more extensive than those required by AASB 111 and relate to:

- Disaggregation of revenue into categories to illustrate how the nature, amount, timing and uncertainty about revenue and cash flows are affected by economic factors. Such disaggregation may include by type of good or service; geographical region; type of contract; or contract duration.

- Contract balances, including explanations of significant changes in contract assets and liabilities during the period;

- Qualitative and quantitative information regarding the aggregate amount of contracted consideration not yet recognised as revenue and an explanation of when the entity expects to recognise those amounts;

- Significant judgements and estimates made in determining the transaction price; allocating the transaction price to performance obligations; and determining when performance obligations are satisfied; and

- Information about assets recognised from the costs to obtain or fulfil a contract.

Conclusion

The introduction of AASB 15 has the potential to change the timing of revenue recognition for B&C entities. Nexia’s Financial Reporting Advisory specialists can assist you analyse the potential impacts of the new revenue model on your operations and whether any changes to your present accounting processes may be required.

If you are affected by these changes or have any questions about the new revenue model, get in touch with our team of specialists.